Appendices | Lawyer's Guide to Client Trust Accounts

Published on February 20, 2024 Starting a Practice Maintaining a Practice Growing a Practice

Appendix 1

Texas Disciplinary Rules of Professional Conduct

Rule 1.14 and Comments

Texas Disciplinary Rules of Professional Conduct

(a) A lawyer shall hold funds and other property belonging in whole or in part to clients or third persons that are in a lawyer’s possession in connection with a representation separate from the lawyer’s own property. Such funds shall be kept in a separate account, designated as a “trust” or “escrow” account, maintained in the state where the lawyer’s office is situated, or elsewhere with the consent of the client or third person. Other client property shall be identified as such and appropriately safeguarded. Complete records of such account funds and other property shall be kept by the lawyer and shall be preserved for a period of five years after termination of the representation.

(b) Upon receiving funds or other property in which a client or third person has an interest, a lawyer shall promptly notify the client or third person. Except as stated in this Rule or otherwise permitted by law or by agreement with the client, a lawyer shall promptly deliver to the client or third person any funds or other property that the client or third person is entitled to receive and, upon request by the client or third person, shall promptly render a full accounting regarding such property.

(c) When in the course of representation a lawyer is in possession of funds or other property in which both the lawyer and another person claim interests, the property shall be kept separate by the lawyer until there is an accounting and severance of their interest. All funds in a trust or escrow account shall be disbursed only to those persons entitled to receive them by virtue of the representation or by law. If a dispute arises concerning their respective interests, the portion in dispute shall be kept separated by the lawyer until the dispute is resolved, and the undisputed portion shall be distributed appropriately.

Comment:

1. A lawyer should hold property of others with the care required of a professional fiduciary. Securities should be kept in a safe deposit box, except when some other form of safekeeping is warranted by special circumstances. All property which is the property of clients or third persons should be kept separate from the lawyer’s business and personal property and, if monies, in one or more trust accounts. Separate trust accounts may be warranted when administering estate monies or acting in similar fiduciary capacities. Paragraph (a) requires that complete records of the funds and other property be maintained.

2. Lawyers often receive funds from third parties from which the lawyer’s fee will be paid. These funds should be deposited into a lawyer’s trust account. If there is risk that the client may divert the funds without paying the fee, the lawyer is not required to remit the portion from which the fee is to be paid. However, a lawyer may not hold funds to coerce a client into accepting the lawyer’s contention. The disputed portion of the funds should be kept in trust and the lawyer should suggest means for prompt resolution of the dispute, such as arbitration. The undisputed portion of the funds should be promptly distributed to those entitled to receive them by virtue of the representation. A lawyer should not use even that portion of trust account funds due to the lawyer to make direct payment to general creditors of the lawyer or the lawyer’s firm, because such a course of dealing increases the risk that all the assets of that account will be viewed as the lawyer’s property rather than that of clients, and thus as available to satisfy the claims of such creditors. When a lawyer receives from a client monies that constitute a prepayment of a fee and that belongs to the client until the services are rendered, the lawyer should handle the fund in accordance with paragraph (c). After advising the client that the service has been rendered and the fee earned, and in the absence of a dispute, the lawyer may withdraw the fund from the separate account. Paragraph (c) does not prohibit participation in an IOLTA or similar program.

3. Third parties, such as client’s creditors, may have just claims against funds or other property in a lawyer’s custody. A lawyer may have a duty under applicable law to protect such third-party claims against wrongful interference by the client, and accordingly may refuse to surrender the property to the client. However, a lawyer should not unilaterally assume to arbitrate a dispute between the client and the third party.

4. The obligations of a lawyer under this Rule are independent of those arising from activity other than rendering legal service. For example, a lawyer who serves as an escrow agent is governed by the applicable law relating to fiduciaries even though the lawyer does not render legal services in the transaction.

5. The client security fund in Texas provides a means through the collective efforts of the bar to reimburse persons who have lost money or property as a result of dishonest conduct of a lawyer.

Appendix 2

Ethics Opinion 611

Ethics Opinion 611

September 2011

Tex. Comm. on Prof’l Ethics, Op. 611, V. 74 Tex. B.J. 944-945 (2011)

QUESTION PRESENTED

Is it permissible under the Texas Disciplinary Rules of Professional Conduct for a lawyer to include in an employment contract an agreement that the amount initially paid by a client with respect to a matter is a “non-refundable retainer” that includes payment for all the lawyer’s services on the matter up to the time of trial?

STATEMENT OF FACTS

A lawyer proposes to enter into an employment agreement with a client providing that the client will pay at the outset an amount denominated a “non-refundable retainer” that will cover all services of the lawyer on the matter up to the time of any trial in the matter. The proposed agreement also states that, if a trial is necessary in the matter, the client will be required to pay additional legal fees for services at and after trial. The lawyer proposes to deposit the client’s initial payment in the lawyer’s operating account.

DISCUSSION

Rule 1.04(a) of the Texas Disciplinary Rules of Professional Conduct provides that a lawyer shall not enter an arrangement for an illegal or unconscionable fee and that a fee is unconscionable “if a competent lawyer could not form a reasonable belief that the fee is reasonable.” Rule 1.04(b) sets forth certain factors that may be considered, along with any other relevant factors not specifically listed, in determining the reasonableness of a fee for legal services. In the case of a non-refundable retainer, the factor specified in Rule 1.04(b)(2) is of particular relevance: “the likelihood, if apparent to the client, that the acceptance of the particular employment will preclude other employment by the lawyer . . . .”

Rule 1.14 deals in part with a lawyer’s handling of funds belonging in whole or in part to the client and requires that such funds when held by a lawyer be kept in a “trust” or “escrow” account separate from the lawyer’s operating account.

Two prior opinions of this Committee have addressed the relationship between the rules now embodied in Rules 1.04 and 1.14.

In Professional Ethics Committee Opinion 391 (February 1978), this Committee concluded that an advance fee denominated a “non-refundable retainer” belongs entirely to the lawyer at the time it is received because the fee is earned at the time the fee is received and therefore the non-refundable retainer may be placed in the lawyer’s operating account. Opinion 391 also concluded that an advance fee that represents payment for services not yet rendered and that is therefore refundable belongs at least in part to the client at the time the funds come into the possession of the lawyer and, therefore, the amount paid must be deposited into a separate trust account to comply with the requirements of what is now Rule 1.14(a). Opinion 391 concluded further that, when a client provides to a lawyer one check that represents both a non-refundable retainer and a refundable advance payment, the entire check should be deposited into a trust account and the funds that represent the non-refundable retainer may then be transferred immediately into the lawyer’s operating account.

This Committee addressed non-refundable retainers again in Opinion 431 (June 1986). Opinion 431 concluded that Opinion 391 remained viable and that non-refundable retainers are not inherently unethical “but must be utilized with caution.” Opinion 431 additionally concluded that Opinion 391 was overruled “to the extent that it states that every retainer designated as non-refundable is earned at the time it is received.” Opinion 431 described a non-refundable retainer (sometimes referred to in Opinion 431 as a “true retainer”) in the following terms:

“A true [non-refundable] retainer, however, is not a payment for services. It is an advance fee to secure a lawyer's services, and remunerate him for loss of the opportunity to accept other employment. . . . . If the lawyer can substantiate that other employment will probably be lost by obligating himself to represent the client, then the retainer fee should be deemed earned at the moment it is received. If, however, the client discharges the attorney for cause before any opportunities have been lost, or if the attorney withdraws voluntarily, then the attorney should refund an equitable portion of the retainer.”

Thus a non-refundable retainer (as that term is used in this opinion) is not a payment for services but is rather a payment to secure a lawyer’s services and to compensate him for the loss of opportunities for other employment. See also Cluck v. Commission for Lawyer Discipline, 214 S.W.3d 736 (Tex. App.-Austin 2007, no pet.).

It is important to note that the Texas Disciplinary Rules of Professional Conduct do not prohibit a lawyer from entering into an agreement with a client that requires the payment of a fixed fee at the beginning of the representation. The Committee also notes that the term “non-refundable retainer,” as commonly used to refer, as in this opinion, to an initial payment solely to secure a lawyer's availability for future services, may be misleading in some circumstances. Opinion 431 recognized in the excerpt quoted above that a retainer solely to secure a lawyer’s future availability, which is fully earned at the time received, would nonetheless have to be refunded at least in part if the lawyer were discharged for cause after receiving the retainer but before he had lost opportunities for other employment or if the lawyer withdrew voluntarily. However, the fact that an amount received by a lawyer as a true non-refundable retainer may later in certain unusual circumstances have to be at least partially refunded does not negate the fact that such amount has been earned and under the Texas Disciplinary Rules may be deposited in the lawyer’s operating account rather than being subject to a requirement that the amount must be held in a trust or escrow account.

In view of Opinions 391 and 431, the result in this case is clear. A legal fee relating to future services is a non-refundable retainer at the time received only if the fee in its entirety is a reasonable fee to secure the availability of a lawyer’s future services and compensate the lawyer for the preclusion of other employment that results from the acceptance of employment for the client. A non-refundable retainer meeting this standard and agreed to by the client is earned at the time it is received and may be deposited in the lawyer’s operating account. However, any payment for services not yet completed does not meet the strict requirements for a non-refundable retainer (as that term is used in this opinion) and must be deposited in the lawyer’s trust or escrow account. Consequently, it is a violation of the Texas Disciplinary Rules of Professional Conduct for a lawyer to agree with a client that a fee is non-refundable upon receipt, whether or not it is designated a “non-refundable retainer,” if that fee is not in its entirety a reasonable fee solely for the lawyer’s agreement to accept employment in the matter. A lawyer is not permitted to enter into an agreement with a client for a payment that is denominated a “non-refundable retainer” but that includes payment for the provision of future legal services rather than solely for the availability of future services. Such a fee arrangement would not be reasonable under Rule 1.04(a) and (b), and placing the entire payment, which has not been fully earned, in a lawyer’s operating account would violate the requirements of Rule 1.14 to keep funds in a separate trust or escrow account when funds have been received from a client but have not yet been earned.

When considering these issues it is important to keep in mind the purposes behind Rule 1.14. Segregating a client’s funds into a trust or escrow account rather than placing the funds in a lawyer’s operating account will not protect a client from a lawyer who for whatever reason determines intentionally to misuse a client’s funds. Segregating the client’s funds in a trust or escrow account may however protect the client’s funds from the lawyer’s creditors in situations where the lawyer’s assets are less than his liabilities and the lawyer’s assets must be liquidated to attempt to satisfy the lawyer’s liabilities. In those situations, client funds in an escrow or trust account may be protected from the reach of the lawyer’s creditors. Accordingly, if a lawyer proposes to enter into an agreement with a client to receive an appropriate non-refundable retainer meeting the requirements for such a retainer and also to receive an advance payment for future services (regardless of whether the amount for future services is determined on a time basis, a fixed fee basis, or some other basis appropriate in the circumstances), the non-refundable retainer must be treated separately from the advance payment for services. Only the payment meeting the requirements for a true non-refundable retainer may be so denominated in the agreement with the client and deposited in the lawyer’s operating account. Any advance payment amount not meeting the requirements for a non-refundable retainer must be deposited in a trust or escrow account from which amounts may be transferred to the lawyer’s operating account only when earned under the terms of the agreement with the client.

CONCLUSION

It is not permissible under the Texas Disciplinary Rules of Professional Conduct for a lawyer to include in an employment contract an agreement that the amount paid by a client with respect to a matter is a “non-refundable retainer” if that amount includes payment for the lawyer’s services on the matter up to the time of trial.

Appendix 3

Cluck v. Comm’n for Lawyer Discipline

Court of Appeals of Texas,

Austin.

Tracy Dee CLUCK, Appellant,

v.

COMMISSION FOR LAWYER DISCIPLINE,

Appellee.

No. 03-05-00033-CV.

Jan. 19, 2007.

James M. Terry Jr., Lexington, James R. Smith, Austin, for appellant. Linda Acevedo, Office of Chief Disciplinary Counsel, State Bar of Texas, Susan Kidwell, Locke Liddell & Sapp LLP, Austin, for appellee.

Before Justices PATTERSON, PURYEAR and HENSON.

OPINION

DAVID PURYEAR, Justice.

FN1. The Texas State Bar promulgates the Texas Disciplinary Rules of Professional Conduct to “define proper conduct for purposes of professional discipline.” Tex. Disciplinary R. Prof'l Conduct preamble: scope ¶ 10, reprinted in Tex. Gov't Code Ann., tit. 2, subtit. G app. A (West 2005) (Tex. State Bar R. art. X, § 9).

BACKGROUND

On August 22, 2002, Smith terminated Cluck as her attorney because she was dissatisfied with the lack of progress made by Cluck on her case and his lack of responsiveness to her phone calls. She requested the return of her file, which she picked up two weeks later. On October 10, 2002, Smith wrote a letter to Cluck asking for a detailed accounting and a refund of the $20,000, less reasonable attorney's fees and expenses. Cluck replied on December 4, 2002, explaining that he did not respond sooner because he was on vacation when Smith's letter arrived and because an electrical storm destroyed his computer and phone systems. He stated that an itemization of his expenses and time billed was included in her file and in bills he had previously mailed to her. Cluck advised Smith that he did not believe she was entitled to a refund.

Smith filed a complaint with the State Bar of Texas, and the Commission initiated this suit, alleging that Cluck committed professional misconduct by violating several Texas Disciplinary Rules of Professional Conduct. The Commission claimed that Cluck failed to promptly comply with a reasonable request for information; contracted for, charged, and collected an unconscionable fee; failed to adequately communicate the basis of his fee; failed to hold funds belonging in whole or in part to a client in a trust account; and failed to promptly deliver funds his client was entitled to receive and render a full accounting regarding those funds upon the client's request. See Tex. Disciplinary R. Prof'l Conduct 1.03(a), reprinted in Tex. Gov't Code Ann., tit. 2, subtit. G app. A (West 2005) (Tex. State Bar R. art. X, § 9) (requiring prompt compliance with reasonable requests for information), 1.04(a) (prohibiting contracting for, charging, or collecting unconscionable fees), 1.04(c) (mandating communication of basis of lawyer's fee), 1.14(a) (providing that lawyer must hold funds belonging in whole or in part to client in trust account), 1.14(b) (requiring prompt delivery of funds that client is entitled to receive and accounting upon request).

Cluck raises three issues on appeal. First, he argues that the fee he charged Smith was not unconscionable. Second, Cluck asserts that, because the fee was not unconscionable, he did not violate the rules regarding refunding unearned fees, holding funds in a trust account, and failing to adequately communicate the basis of the fee. Finally, Cluck insists that he promptly complied with the reasonable request for information under the circumstances. Thus, he argues that the trial court erred by holding that Cluck committed professional misconduct and granting summary judgment in favor of the Commission.

The violation of one disciplinary rule is sufficient to support a finding of professional misconduct. See Tex. R. Disciplinary P. 1.06(V)(1), reprinted in Tex. Gov't Code Ann., tit. 2, subtit. G app. A-1 (West 2005) (defining “Professional Misconduct” to include “[a]cts or omissions by an attorney ... that violate one or more of the Texas Disciplinary Rules of Professional Conduct”). Summary judgment orders in attorney discipline appeals are governed by traditional summary judgment standards. See Fry v. Commission for Lawyer Discipline, 979 S.W.2d 331, 333-34 (Tex. App.-Houston [14th Dist.] 1998, pet. denied). When a trial court's order granting a summary judgment does not specify the ground or grounds relied on for the ruling, it must be affirmed on appeal if any of the grounds asserted in the motion are meritorious. State Farm Fire & Cas. Co. v. S.S., 858 S.W.2d 374, 380 (Tex. 1993). When the order states the grounds relied on, it can be affirmed only on the specified grounds. Id. Here, because the order granting summary judgment states that the trial court relied on every ground alleged by the Commission and because each ground alone is sufficient to support a finding of professional misconduct, we must affirm the district court's summary judgment if we find that no genuine issue of material fact exists regarding Cluck's violation of at least one disciplinary rule and that the Commission was entitled to judgment as a matter of law. See Tex. R. Civ. P. 166a(c). We review the summary judgment de novo, take as true all evidence favorable to the nonmovant, and indulge every reasonable inference and resolve any doubts in the nonmovant's favor. Valence Operating Co. v. Dorsett, 164 S.W.3d 656, 661 (Tex. 2005). When both parties move for summary judgment on the same issue and when the trial court grants one motion and denies the other, we review the evidence presented, determine the questions presented, and render the judgment the trial court should have rendered if we determine that it erred. Id.

We first address the trial court's finding that Cluck violated rule 1.14(a) by failing to hold the $20,000 paid by Smith in a trust account. See Tex. Disciplinary R. Prof'l Conduct 1.14(a) (“A lawyer shall hold funds ... belonging in whole or in part to clients .... in a separate account, designated as a ‘trust’ or ‘escrow’ account....”). Cluck argues that the fee paid by Smith was a nonrefundable retainer that was earned at the time it was received and that he was not obligated to hold the funds in a trust account because they did not belong in whole or in part to Smith. The Commission argues that, despite the contractual language, the fee was neither nonrefundable nor a retainer but was instead an advance fee that should have been held in a trust account.

An opinion by the Texas Committee on Professional Ethics discusses the difference between a retainer and an advance fee. See Tex. Comm. on Prof'l Ethics, Op. 431, 49 Tex. B.J. 1084 (1986). The opinion explains that a true retainer “is not a payment for services. It is an advance fee to secure a lawyer's services, and remunerate him for loss of the opportunity to accept other employment.” Id. The opinion goes on to state that “[i]f the lawyer can substantiate that other employment will probably be lost by obligating himself to represent the client, then the retainer fee should be deemed earned at the moment it is received.” Id. If a fee is not paid to secure the lawyer's availability and to compensate him for lost opportunities, then it is a prepayment for services and not a true retainer. Id. “A fee is not earned simply because it is designated as non-refundable. If the (true) retainer is not excessive, it will be deemed earned at the time it is received, and may be deposited in the attorney's account.” Id. However, money that constitutes the prepayment of a fee belongs to the client until the services are rendered and must be held in a trust account.

Tex. Disciplinary R. Prof'l Conduct 1.14 cmt. 2.

We are convinced that no genuine issue of material fact exists regarding whether the fees charged by Cluck were true retainers and, thus, whether Cluck was obligated to hold the funds in a trust account. First, the contract for legal services does not state that the $15,000 payment compensated Cluck for his availability or lost opportunities; instead, it states that Cluck's hourly fee will be billed against it. Second, the $5,000 additional payment requested by Cluck in 2002 makes clear that the $15,000 paid in 2001 did not constitute a true retainer; as the trial court noted in its judgment, “if the first $15,000 secured [Cluck]'s availability, it follows that he should not charge another ‘retainer’ to resume work on the divorce. He was already ‘retained’ for the purposes of representing Smith in the matter.”

Finally, Cluck concedes in his brief that the fees did not represent a true retainer. However, he argues that he did not violate any disciplinary rules by depositing the money in his operating account because the contract states that the fees are nonrefundable. We disagree. “A fee is not earned simply because it is designated as non-refundable.” Tex. Comm. on Prof'l Ethics, Op. 431, 49 Tex. B.J. 1084 (1986). Advance fee payments must be held in a trust account until they are earned. Tex. Disciplinary R. Prof'l Conduct 1.14 cmt. 2 (providing that trust account must be utilized “[w]hen a lawyer receives from a client monies that constitute a prepayment of a fee and that belongs to the client until the services are rendered” and that “[a]fter advising the client that the service has been rendered and the fee earned, and in the absence of a dispute, the lawyer may withdraw the fund from the separate account”); Tex. Comm. on Prof'l Ethics, Op. 431, 49 Tex. B.J. 1084 (1986); see also Tex. Disciplinary R. Prof'l Conduct 1.15(d) (“Upon termination of representation, a lawyer shall take steps to the extent reasonably practicable to protect a client's interests, such as ... refunding any advance payments of fee that has not been earned.”).

Cluck violated rule 1.14(a) because he deposited an advance fee payment, which belonged, at least in part, to Smith, directly into his operating account. Accordingly, we must affirm the trial court's summary judgment holding that Cluck committed professional misconduct because he violated a disciplinary rule. Because Cluck's other points of error address alternate grounds for the trial court's holding that Cluck committed professional misconduct and because we have already upheld the summary judgment on one ground raised by the trial court, we do not reach his other arguments.

CONCLUSION

Having held that no genuine issue of material fact exists regarding whether Cluck committed professional misconduct, we affirm the district court's summary judgment.

Appendix 4

Texas Disciplinary Rule of Professional Conduct Rule 1.04 (d) - specifying requirements for a contingent fee agreement

Texas Disciplinary Rules of Professional Conduct

1.04 Fees (Amended March 1, 2005)

(d) A fee may be contingent on the outcome of the matter for which the service is rendered, except in a matter in which a contingent fee is prohibited by paragraph (e) or other law. A contingent fee agreement shall be in writing and shall state the method by which the fee is to be determined. If there is to be a differentiation in the percentage or percentages that shall accrue to the lawyer in the event of settlement, trial or appeal, the percentage for each shall be stated. The agreement shall state the litigation and other expenses to be deducted from the recovery, and whether such expenses are to be deducted before or after the contingent fee is calculated. Upon conclusion of a contingent fee matter, the lawyer shall provide the client with a written statement describing the outcome of the matter and, if there is a recovery, showing the remittance to the client and the method of its determination.

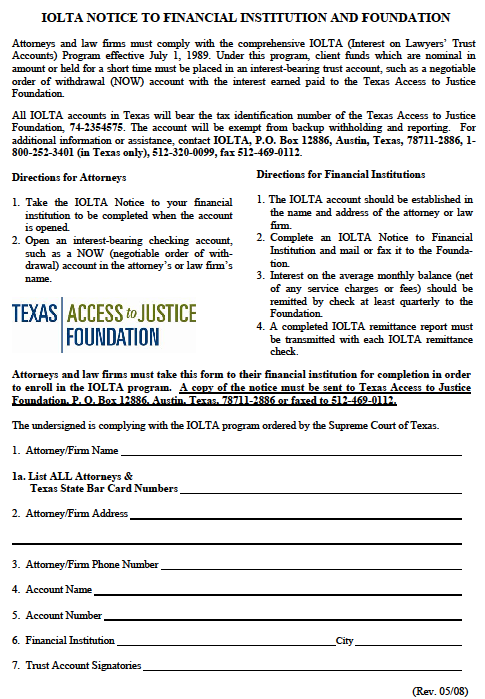

Appendix 5IOLTA Notice to Financial Institution from Lawyer

Appendix 6

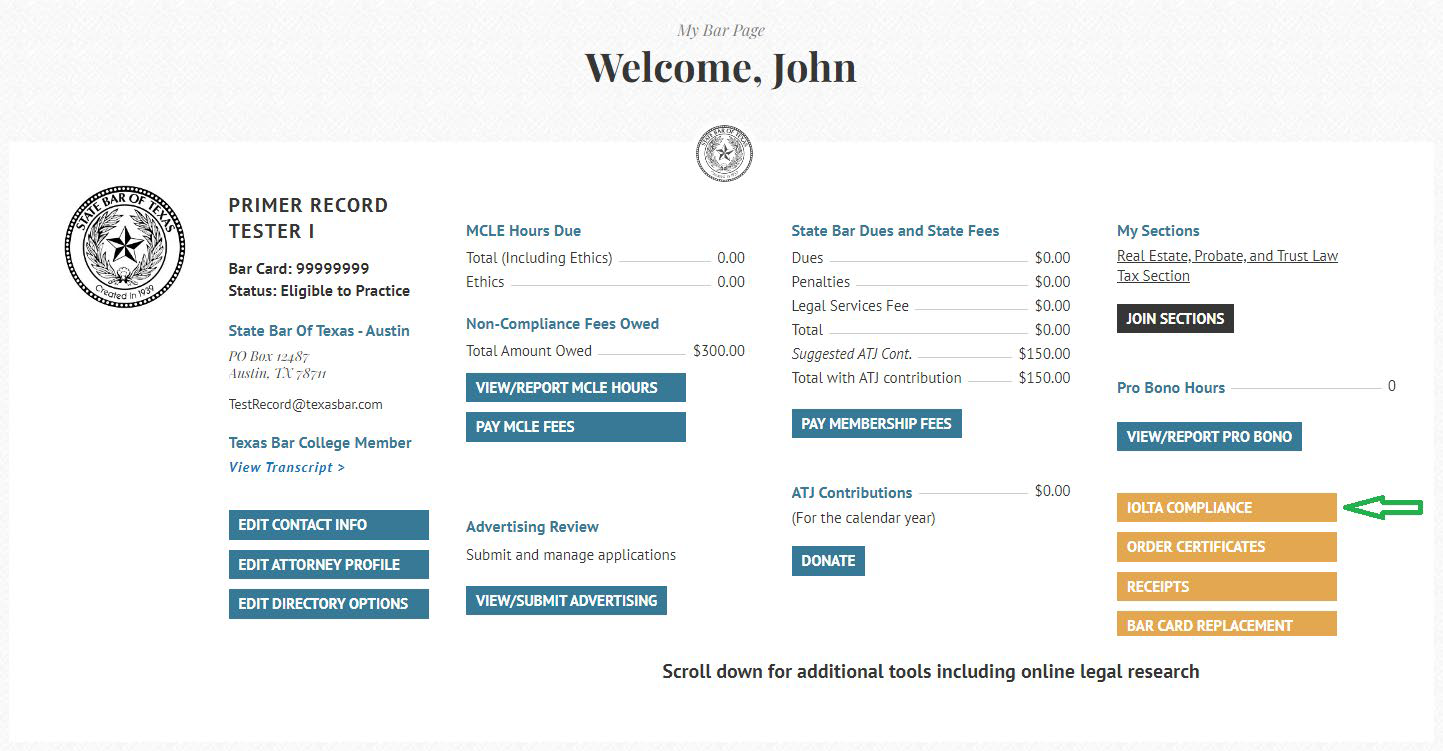

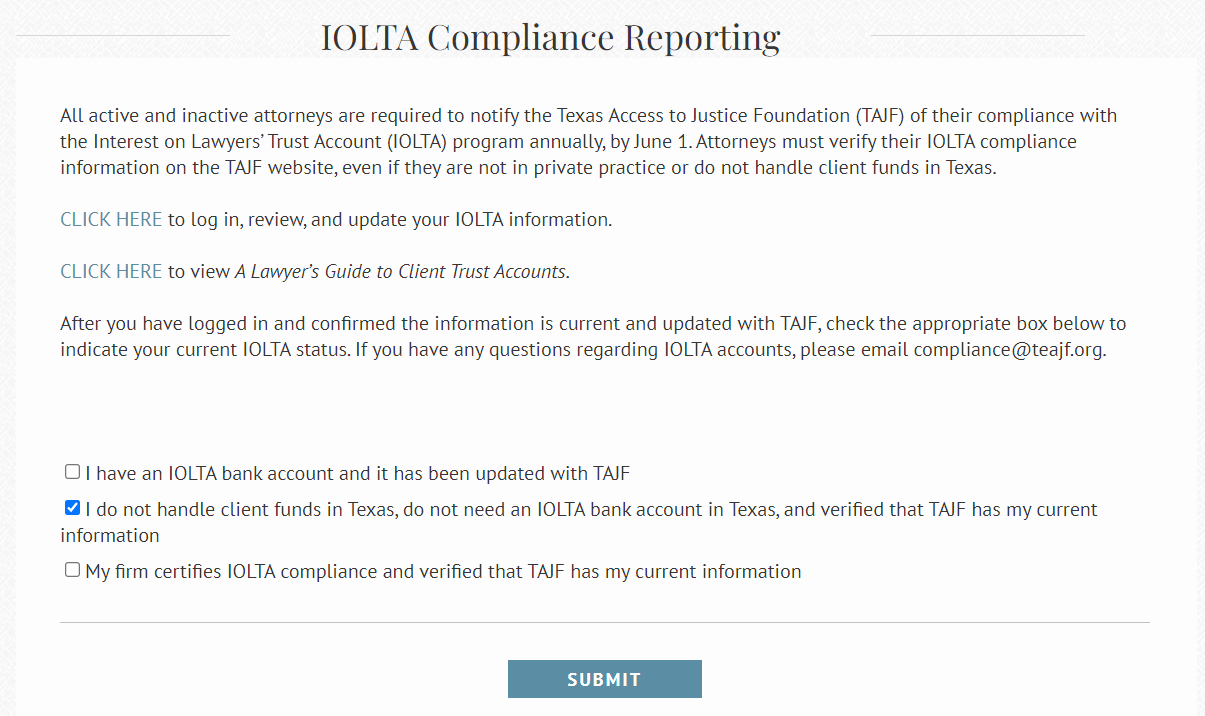

Annual IOLTA Compliance on SBOT Dues Statement

Appendix 7

Ethics Opinion 602

OPINION 602

October 2010

Tex. Comm. on Prof’l Ethics, Op. 602, V. 73 Tex. B.J. 976-977 (2010)

QUESTION PRESENTED

Under the Texas Disciplinary Rules of Professional Conduct, may a lawyer deliver to the Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts, and file related reports concerning, funds or other property held in the lawyer’s trust account for which the lawyer is unable to locate or to identify the owner?

STATEMENT OF FACTS

A lawyer holds in his trust account funds or other property belonging to a client or a third party. After three years, despite reasonable efforts, the lawyer either is unable to locate the client or third party that is the owner of the funds or other property or is unable to determine the identity of the owner.

DISCUSSION

Rule 1.14 of the Texas Disciplinary Rules of Professional Conduct sets forth a lawyer’s obligations regarding funds and other property belonging to clients or third persons. Among other requirements, Rule 1.14(a) requires that a lawyer holding such funds keep the funds in a separate trust or escrow account and that “[c]omplete records of such account funds and other property shall be kept by the lawyer and shall be preserved for a period of five years after termination of the representation.” Rule 1.14(b) provides:

“Upon receiving funds or other property in which a client or third person has an interest, a lawyer shall promptly notify the client or third person. Except as stated in this rule or otherwise permitted by law or by agreement with the client, a lawyer shall promptly deliver to the client or third person any funds or other property that the client or third person is entitled to receive and, upon request by the client or third person, shall promptly render a full accounting regarding such property.”

Further, Rule 1.14(c) includes the requirement that “[a]ll funds in a trust or escrow account shall be disbursed only to those persons entitled to receive them by virtue of the representation or by law.”

Section 72.001(e) of the Texas Property Code defines a “holder” of property as “a person, wherever organized or domiciled, who is: (1) in possession of property that belongs to another; (2) a trustee; or (3) indebted to another on an obligation.” Section 72.101(a) of the Texas Property Code provides that, with exceptions not here relevant:

“. . . personal property is presumed abandoned if, for longer than three years: (1) the existence and location of the owner of the property is unknown to the holder of the property; and (2) according to the knowledge and records of the holder of the property, a claim to the property has not been asserted or an

act of ownership of the property has not been exercised.”

Section 74.301(a) of the Texas Property Code states, in relevant part, that “each holder who on June 30 holds property that is presumed abandoned under Chapter 72, 73, or 75 shall deliver the property to the comptroller on or before the following November 1 accompanied by the report required to be filed under Section 74.101.” Under section 74.101(a) of the Texas Property Code, each holder of property presumed abandoned under chapter 72 (which includes section 72.101(a) quoted above) “shall file a report of that property . . . .” with the Comptroller of Public Accounts. Section 74.101(c) requires that the report include, if known by the holder, certain identifying information about each person who appears to be the owner of the property or any person who is entitled to the property. Under section 74.103 of the Texas Property Code, a holder of property who is required to make such a report must keep for ten years certain records concerning reported property and persons who appear to be owners of such property.

Although this Committee does not have authority to interpret statutory law and no opinion is here offered as to the interpretation of the provisions of the Texas Property Code cited above, for purposes of this opinion the Committee assumes a Texas lawyer could reasonably conclude that in certain circumstances these provisions apply to property held in his trust account for which the owner of the property cannot be located or cannot be identified.

No provision of the Texas Disciplinary Rules of Professional Conduct limits or prohibits the transfer to the Texas Comptroller of funds or property that a lawyer reasonably believes to be “presumed abandoned” under the Texas Property Code. Any delivery of funds required by provisions of the Texas Property Code will be within the scope of Rule 1.14(b), which requires, with exceptions not here applicable, that “a lawyer shall promptly deliver to the . . . third person any funds or other property that the . . . third person is entitled to receive . . . .” Accordingly, if a lawyer concludes that he holds property subject to the delivery requirements of the Texas Property Code, Rule 1.14(b) of the Texas Disciplinary Rules of Professional Conduct not only permits but requires the lawyer to deliver such funds or property to the Comptroller in accordance with the Property Code’s requirements.

With respect to the filing of reports with the Comptroller on property required to be transferred to the Comptroller under the Texas Property Code, it is necessary to consider the requirements of Rule 1.05 of the Texas Disciplinary Rules of Professional Conduct concerning confidential information relating to a lawyer’s representation of current and former clients. Rule 1.05(a) defines “confidential information” to include both “privileged information” and “unprivileged client information.” The latter category is broadly defined in Rule 1.05(a) to mean “all information relating to a client or furnished by the client, other than privileged information, acquired by the lawyer during the course of or by reason of the representation of the client.” Much of the information called for in a report to the Comptroller under section 74.101 of the Texas Property Code appears to come within the definition of “confidential information” under Rule 1.05(a), including, for example, the name, social security number, driver’s license number, e-mail address, and last known address of the client or other person to whom the property is believed to belong.

Rule 1.05(c)(4) expressly authorizes a lawyer to reveal confidential information “[w]hen the lawyer has reason to believe it is necessary to do so in order to comply with a court order, a Texas Disciplinary Rule of Professional Conduct, or other law.” (emphasis added) Thus, if a lawyer files a report containing confidential client information that the lawyer reasonably believes is required under provisions of the Texas Property Code concerning abandoned property, filing such report would not violate the lawyer’s obligations regarding confidentiality under Rule 1.05. It must be emphasized that this authorization applies only to disclosures that are “necessary” for compliance with applicable law. Particularly in view of the general obligation imposed by Rule 1.05 for lawyers not to reveal confidential information acquired in the representation of clients unless an exception such as Rule 1.05(c)(4) applies, the lawyer must take care not to make disclosures that exceed what is required to comply with applicable law. As noted in Comment 14 to Rule 1.05, “ . . . a disclosure adverse to the client’s interest should be no greater than the lawyer believes necessary to the purpose.”

CONCLUSION

Under the Texas Disciplinary Rules of Professional Conduct, a lawyer is permitted to deliver to the Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts, and to file required reports concerning, funds or other property held in the lawyer’s trust account for which the lawyer is unable to locate or to identify the owner, provided the lawyer reasonably believes that such action is required by applicable provisions of Texas law on abandoned property.

Appendix 8

Wilson v. Comm’n for Lawyer Discipline,

BODA Case No. 46432 (January 28, 2011)

Board of Disciplinary Appeals

Appointed by the Supreme Court of Texas

JOE MARR WILSON, APPLELLANT

v.

COMMISSION FOR LAWYER DISCIPLINE OF THE STATE BAR OF TEXAS, APPELLEE

No. 46432

Opinion and Judgment Signed January 28, 2011, and Delivered January 30, 2011

Considered En Banc October 18, 2010

On Appeal from the Evidentiary Panel for the State Bar of Texas, District 13 Grievance Committee No. D01008355970

Opinion and Order

COUNSEL:

Appellant Joe Marr Wilson, Amarillo, Texas, pro se.

For Appellee, Commission for Lawyer Discipline of the State Bar of Texas, Linda A. Acevedo, Chief Disciplinary Counsel, and Cynthia Canfield Hamilton, Senior Appellate Counsel, Austin, Texas.

Judgment Public Reprimand Affirmed.

OPINION AND ORDER:

Appellant, attorney Joe Marr Wilson, appeals from a Judgment of Public Reprimand, alleging that there was no evidence to support a finding that he violated Texas Disciplinary Rule of Professional Conduct (“TDRPC”) 1.14(c).TEX. DISCIPLINARY R. OF PROF'L CONDUCT, reprinted in TEX. GOV'T CODE, tit. 2, subtit. G, app. A (Vernon 2005). The Evidentiary Panel found that Wilson had disbursed trust account funds belonging to his client to himself when he was not entitled to them. We find that Wilson's own testimony and billing statement that he paid himself attorney's fees from funds given to him by his client specifically designated for another purpose is substantial evidence that he disbursed client funds to himself. His conduct violated TDRPC 1.14(c) as a matter of law, and we affirm the Judgment of Public Reprimand signed on December 29, 2009 by the Evidentiary Panel of the State Bar of Texas District 13 (Amarillo) grievance committee.

UNDERLYING GRIEVANCE

The complainant, Donda Haney, hired Wilson in August of 2004 to represent her in a child custody and support matter. Haney paid Wilson $3,500 in advance, and he filed a petition to modify Haney's original visitation order on August 17, 2004. They did not execute a written employment contract. She was to be billed at the rate of $200 per hour. The advance payment was depleted by December 2005. Wilson did not require Haney to replenish this retainer.

Before the trial judge would consider Haney's request to modify the existing custody order, he required her to pay her past-due child support. On, March 5, 2007, the trial court entered an agreed order holding Haney in contempt and ordering her to pay $19,006.51 to her ex-husband. The commitment was suspended on condition that she made scheduled payments under that order. Haney did not comply and was jailed for contempt for 45 days.

In contemplation of negotiating a reduction in her support arrearages, Haney sent Wilson two checks in March 2008: one in the amount of $7,500 (to pay the support arrearages to her ex-husband) and one in the amount of $500 (to pay her ex-husband's attorney's fees). Prior to sending the checks, Haney and Wilson discussed by email the purpose of the money. Wilson deposited both checks in his trust account. In April 2008 Wilson prepared a settlement agreement and transmitted it to her ex-husband's attorney who (Wilson claims) had agreed verbally to accept $8,000 total to settle the arrearage and attorney's fees. He did not forward the money, and it remained in his trust account pending execution of the agreement. Wilson told Haney that he would “maintain control of the money until the appropriate papers are signed.” Wilson stated that the opposing attorney never returned the settlement documents or rejected the verbal agreement. Wilson did not communicate with Haney again until after she fired him.

In August 2008 Haney sent Wilson a letter terminating his services and asking for the return of the $8,000 and her file. Approximately 30 days after receiving the letter, Wilson sent Haney a check in the amount of $1,553.39 with a letter explaining that the check was “a refund of unearned attorney's fees.” Included was a billing statement of services rendered that indicated that Wilson had applied the $8,000 designated for Haney's ex-husband to the amount Wilson determined that Haney owed to him for attorney's fees. This included a $768.75 charge for copying Haney's file. [FN1] There is no dispute that Wilson offset his fees against the $8,000 without Haney's prior knowledge or consent.

SUBSTANTIAL EVIDENCE

Wilson argues that there was no evidence to support a finding that he violated TDRPC 1.14(c) because the Commission for Lawyer Discipline failed to prove that he disbursed any trust account funds at issue to anyone. In support of his argument, Wilson points to finding of fact number three of the evidentiary panel's order: “Respondent [Wilson] disbursed trust account funds, belonging to his client Donda Haney, to himself when he was not entitled to them by virtue of the representation or by law.” Specifically, Wilson says that there is no evidence in the record that the trust account funds were disbursed because he only withheld the funds from his client.

BODA reviews the evidence of a violation of a rule of professional conduct under the substantial evidence standard. TEX. R. DISCIPLINARY PROCEDURE 2.24, reprinted in TEX. GOV'T CODE, tit. 2, subtit. G, app. A-1 (Vernon 2005) (“TRDP”). In deciding whether substantial evidence exists to support the findings of fact, the reviewing body determines whether reasonable minds could have reached the same conclusion. Texas Health Facilities Commission v. Charter Medical-Dallas, Inc., 665 S.W.2d 446, 452 (Tex. 1984) (applying the substantial evidence standard under the APTRA); Allison v. Comm'n for Lawyer Discipline, BODA Case No. 41135 (August 21, 2008). The reviewing court may not substitute its judgment for the decisions within the lower court's discretion and is not bound by the reasons stated in the order for the result, provided that some reasonable basis exists in the record for the action taken. Railroad Comm'n of Texas v. Torch Operating Co., 912 S.W.2d 790, 792 (Tex. 1995). Under substantial evidence review, the findings, conclusions, and decisions of the lower court are presumed to be supported, and the burden is on the appellant to prove otherwise. Substantial evidence is something more than a mere scintilla, but the evidence in the record may preponderate against the decision and still amount to substantial evidence.

City of El Paso v. Pub. Util. Comm'n of Tex., 883 S.W.2d 179, 185 (Tex. 1994).

Wilson is incorrect that there is no evidence that he disbursed the funds contrary to TDRPC 1.14(c). Wilson admitted through his own testimony that he “offset” client trust funds, without the knowledge and consent of the client, to pay his fees. Wilson's transmittal letter to Haney with the refund check characterized the balance of the $8,000 as “payment” for his attorney's fees. The 12-page billing statement Wilson enclosed with the letter covered the period from August 2, 2004 until September 24, 2008 and included an entry for March 20, 2008 of “Payment Received, Thank You” with a credit of $8,000. Wilson violated his duty under Rule 1.14(c) to disburse the funds only to someone entitled to receive them when he sent the letter and billing statement to Haney stating that he had applied $6,446.61 ($8,000 deposited in Wilson's trust account less the $1,533.39 “refund”) of those funds to his own credit and failed to return them to her. We find, therefore, substantial evidence to support the Evidentiary Panel's finding.

Wilson clearly failed to use the funds for the original purpose which Haney had directed and failed to return the money to her when she requested it. At the Evidentiary Panel hearing, Wilson argued that he believed that he was entitled to offset attorney's fees owed by Haney against the $8,000 he held in trust because the original purpose of the funds no longer existed once Haney fired him and because she did not dispute his fees. [FN2] Whether the original purpose no longer existed (which is unclear) or whether Haney disputed his fees is immaterial, because the funds were never given to Wilson to pay his fee. They at all times belonged to Haney who would have had to have affirmatively agreed (not merely fail to object) to allow Wilson to apply the money to his fee. Funds, once entrusted to the lawyer for a particular purpose, can be used only for that purpose, and any unused portion must be returned to the client with a full accounting. See, Brown v. Comm'n for Lawyer Discipline, 980 S.W.2d 675, 680 (Tex. App.—San Antonio 1998, no pet.) (lawyer who retained settlement funds with client's consent and directive to use them for future litigation violated TDRPC 1.14 when he used them for different purpose); 48 ROBERT P. SCHUWERK & LILLIAN B. HARDWICK, TEXAS PRACTICE: HANDBOOK OF TEXAS LAWYER AND JUDICIAL ETHICS § 6:14 p. 979 (2010-2011) (“[F]unds entrusted to a lawyer for a specific purpose can be used only for that purpose: the lawyer must return the unused portion—less any agreed-upon fees earned or expenses incurred—to the client, together with a full accounting.”).

We hold that the lawyer may not unilaterally apply the client's funds held for a designated purpose for another unauthorized purpose without the client's specific consent. This result is consistent with the plain language of TDRPC 1.14 and the intent of the rule. We therefore conclude that Wilson has failed to meet his burden and affirm the Judgment of the Evidentiary Panel in all respects.

IT IS SO ORDERED.

W. Clark Lea

Chair

JoAl Cannon Sheridan

Vice Chair

Alice A. Brown

Ben Selman

Charles L. Smith

Deborah J. Race

Thomas J. Williams

Kathy J. Owen

David A. Chaumette

Jack R Crews

Gary R. Gurwitz

FN1. Ten days before the evidentiary hearing, Wilson refunded the $768.75 that he had charged Haney for copying her file. He conceded at the hearing that, although he thought at the time he could charge for copying the file, he later came to understand it was improper under the TDRPC.

FN2. It is not clear that Wilson ever gave Haney an opportunity to object to his fees before he paid himself. Although Wilson claimed to have sent Haney bills he could not produce copies and admitted that his office did not keep copies. At the hearing, Haney testified that she didn't understand that she owed Wilson money.

Appendix 9

OPINION 625

February 2013

Tex. Comm. on Prof’l Ethics, Op. 625, V. 76 Tex. B.J. 362 (2013)

QUESTION PRESENTED

Is it permissible for a lawyer who replaces a client’s prior lawyer in a litigation matter to distribute funds resulting from settlement of the litigation matter without regard to a promise of payment, of which the second lawyer is aware, given to the client’s healthcare provider in a letter signed by the client’s prior lawyer?

STATEMENT OF FACTS

A client in a personal injury case sought treatment from a healthcare provider for injuries sustained in an accident. Prior to providing treatment, the healthcare provider requested and obtained from the lawyer who initially represented the client with respect to the personal injury case a “Letter of Protection” addressed to the healthcare provider. This “Letter of Protection” promised that for medical care provided to the client the healthcare provider would be paid directly out of any settlement proceeds or payment resulting from a jury verdict in the personal injury case.

Thereafter a second lawyer replaced the client’s first lawyer in the personal injury litigation. The second lawyer, who was aware of the “Letter of Protection,” contacted the healthcare provider and attempted to negotiate a compromise of the amount billed by the healthcare provider for services rendered to the client but the healthcare provider refused to discount the amount previously billed. The second lawyer later settled the case, took his agreed fee, and distributed the remaining funds to the client without paying the healthcare provider any amount for the medical services provided to the client for which payment had been promised in the “Letter of Protection” signed by the client’s first lawyer.

DISCUSSION

Rule 1.14(c) of the Texas Disciplinary Rules of Professional Conduct provides as follows:

“When in the course of representation a lawyer is in possession of funds or other property in which both the lawyer and other person claims interests, the property shall be kept separate by the lawyer until there is an accounting and severance of their interest. All funds in a trust or escrow account shall be disbursed only to those persons entitled to receive them by virtue of the representation or by law. If a dispute arises concerning their respective interests, the portion in dispute shall be kept separated by the lawyer until the dispute is resolved, and the undisputed portion shall be distributed appropriately.”

In the circumstances here considered, Rule 1.14(c) requires that the client’s second lawyer keep settlement proceeds to which the client’s healthcare provider has a claim separate until there is an accounting and severance of the interests claimed in these funds by the healthcare provider. Although it is a legal question, rather than a matter of interpretation of the Texas Disciplinary Rules of Professional Conduct, whether and to what extent the “Letter of Protection” signed by the client’s first lawyer binds the client, the client’s second lawyer is aware that as a consequence of the “Letter of Protection” the healthcare provider is claiming an interest in a portion of the settlement funds. In such circumstances, the second lawyer would violate the requirements of Rule 1.14(c) if, before the validity of the healthcare provider’s claim has been conclusively determined, the lawyer distributed to someone other than the healthcare provider the portion of the funds claimed by the healthcare provider. Following the approach suggested in Comment 2 to Rule 1.14 with respect to a dispute between a client and lawyer as to the disposition of funds, it would be appropriate in these circumstances for the lawyer to hold in trust the portion of the settlement funds claimed by the healthcare provider and to suggest a means for prompt resolution of the dispute, such as arbitration.

CONCLUSION

It is a violation of the Texas Disciplinary Rules of Professional Conduct for a lawyer who replaces a client’s prior lawyer in a litigation matter to distribute funds resulting from settlement of the litigation matter without regards to a promise of payment, of which the second lawyer is aware, given to the client’s healthcare provider in a letter signed by the client’s prior lawyer.

Updated January 2024

-1.png)

Law Practice Management Committee

The Law Practice Management committee is comprised of experienced lawyers from across Texas who have been appointed by the State Bar President.